I've developed a practice of bringing unsuccessful efforts from previous workshops, or boring fabrics from my stash, to class, just to see whether a new process, an additional layer or two, might redeem them in some way. This piece (below) started life as a portion of a bedsheet. I overdyed it with purple and screen-printed my own made-up mysterious runic symbol all over it. Ho hum. In last week's class I painted a shadow effect around portions of the markings, hoping to get a sense of depth. Mmmm, not so much. I used a dye that someone had labeled "purple," but that turned out to be blood-red. Quite the color combination there:

But as the dye dried, either the soda ash in the dye mixture or some interaction between the red and the earlier turquoise, or the even earlier purple, pushed out a fine white line between colors. The overlaid red on turquoise is kind of interesting, too. Tiny portions of this overall failed effort actually show promise. If and when I use this piece, I'll probably zoom in on those cool little bits and leave the rest of the fabric in tatters:

Another piece started life as solid yellow commercial yardage, which I wrapped and overdyed in an indigo workshop last year. Experimenting with dye painting, I did a few brushstroke squiggles, immediately realized my error, and attempted to wash them out. But because I'd used orange, of which the red component is a notorious dye bully, the squiggles remained. The piece, overall, reminded me of light filtering down through water. So, in last week's workshop, I screened on several fish. I remembered to account for the eyes, but the overall effect was a basic silhouette, too elementary-schoolish (no pun intended). So I stenciled a few markings onto each fish and discharged them with our bleaching agent of choice, thiourea dioxide, a.k.a thiox. As it happens, neither turquoise dye nor indigo bow down to the lightening powers of thiox, so the blue crept right back in when I washed the piece. What to do? Common household bleach to the rescue! It turns out that Soft Scrub (tm) or lotion-style Comet (tm) with bleach does the job. I used the same stuff later to print my leaf stencil (visible on the red and orange fabrics here) onto denim. It worked great, and it's the perfect consistency for screening right out of the bottle.

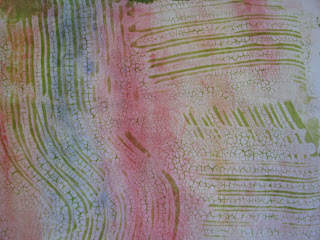

Shortly after I first started quilting, I acquired somewhere a length of men's shirt-like fabric, light gray with faint stripes and a tiny pink-and-magenta repeated motif. At some point I stamped it randomly with a magenta grid pattern. That did not alter its deeply uninteresting nature; if anything, I'd managed to transform it into something overtly ugly. Last week in class I did a series of swirly monoprints over it, in green, and, on top of that, printed my Japanese maple photo emulsion screen. Close-cropped, it's more interesting, at least, than it used to be. If it doesn't work as whole cloth, I can always cut into it when I need a gray-magenta-green sort of busy intertwined fabric with men's-tie motif markings. You never know.